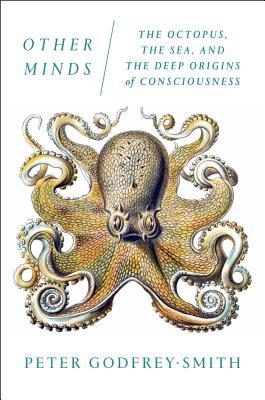

Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness – Peter Godfrey-Smith

THIS is the octopus book you have been waiting for all your life. Philosopher of science (and, importantly, scuba diver) Peter Godfrey-Smith traces the origins of intelligence through the tree of life, pausing at length on the cephalopods. These animals – cuttlefish, octopus, squid – stand out as exceptionally intelligent among animals, but only live for a year or two, the females expiring after they finish nurturing their first and only clutch of eggs (this is called semelparity). Both they and the males undergo a brief and catastrophic period of senescence, during which time they lose limbs, lose pigmentation, and their cognitive functions appear to be in sharp decline. (As an aside, I think that this cuttlefish may have been experiencing this very late-life decline.) Why, speaking evolutionarily, invest the energy required to develop such a complex brain, if its owner is going to live for such a short time?

This is the ultimate question that Godfrey-Smith grapples with. Prior to arriving here, he leads us on wonderful explorations of octopus physiology, the origins of life, and the nature of intelligence. Refreshingly, he takes a nuanced view of intelligence in cephalopods and resists the ever-present temptation to anthropomorphise these fascinating creatures. He points out, for example, that it is easy to mistake dexterity – eight arms and all – for smarts. I read this book while recuperating from a head injury whose degree of seriousness was not yet clear at the time of reading (it was mild, and I’m fine now). This uncertainty as to the state of my own brain made my reading of the sections on intelligence and the nature of minds somewhat poignant. The octopus brain is distributed throughout its body, with neurons in its legs as well as in places you’d be more likely to look for them.

Godfrey-Smith commences this book with a description of giant cuttlefish (the same corgi-sized beings we read about here), and this cements my desire to one day meet such a creature. My favourite chapter, however, deals with how cephalopods change colour. The complexity of this process is incredible, and not yet fully understood. In particular, it seems that they cannot see in colour, and yet they perform feats of camouflage that would seem to be impossible without knowing what colour and pattern to aim for.

The book is beautifully, lyrically written with a gentleness and compassion that I think comes from Godfrey-Smith’s own extensive observation of cephalopods in their natural habitat. He returns compulsively to Octopolis, the first octopus “city” discovered off the coast of Australia. I’ll leave you with this quote:

The chemistry of life is an aquatic chemistry. We can get by on land only by carrying a huge amount of salt water around with us.

You can find a comprehensive list of reviews and interviews on the author’s website. There’s a fetching giant cuttlefish picture in this article from The Guardian. If you are in South Africa, get a copy of the book here. If in the US, here, and for the UK go here.

For an equally awe-struck but completely different take on octopus, written largely from the perspective of an aquarium volunteer, you could also check out Sy Montgomery’s The Soul of an Octopus.